This transcript is of a conversation I had with Dr Joey Engelberg, Professor of Finance at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School (listen to the podcast). You can always subscribe to Tradestreaming Radio on iTunes.

In my book, Tradestreaming and on my website, I talk a lot about what I call collateral research. This is information that’s inherently non-financial in nature, but that investors are using to aid in their investment decisions.

Using Google Search Data to Invest by tradestreaming

One example I talk about in the book specifically is Amazon sales data. You can go onto Amazon.com, look up best selling computers, and you can get a list at that moment in time, updated hourly, of what’s selling well. So, if you were an investor in Apple, and Apple was introducing a new product to the market, that information, although it doesn’t say specific sales numbers, of what Apple itself is seeing through selling on Amazon, that information is at least important in the sense of how well a product may be received into the market.

Another area of concern for investors, of interest, is Google search data. Google recognizes that itself, and launched about two years ago on Google Finance something called Google domestic search trends, GDST. That’s a mouthful. What that is basically is Google itself is looking at a vertical search, something about the auto industry, unemployment, something where there are a series of search terms around a particular category, and then mapping them against the volume of other search queries.

So, you can get a feel for, qualitatively, how a certain search term or industry is trending vis a vis the rest of the search market. You can then overlay that information on top of an ETF or a mutual fund that may track that industry, and you can get a view for how well some of that data may, or may not influence future price movements.

Today’s guest on the podcast is Joey Engelberg, who studied this actually quite intensely. He’s a Professor of Finance at the University of North Carolina, the Kenan-Flagler Business School. He previously worked at the SEC, as a research specialist.

He recently produced a paper that caught my eye, called In Search of Attention. That basically looks at Google search data and tries to map it to future price movements. He actually did find a correlation that certain abnormal trends in search data can lead to abnormal returns in the stock market.

I think that’s fascinating. I think that opens up a whole new realm of research in the industry to figure out some of these things online may impact or may be insightful into future price movements.

One of the things I talked about in my book are prediction markets, right? So, these may or may not be financial prediction markets, where people are actually wagering money on future events. They may be virtual, or there may be money behind them, like the Iowa markets, electronic markets. Here people are betting on political events that occur in the future.

We certainly know that in the realm of elections, if we compare prediction markets like these that occur online where somebody comes in and says, “I’m wagering this amount of money that so-and-so is going to be elected President in 2014,” we know that that data is more accurate than a lot of polling data that they get when they actually do exit surveys for people coming out of polling stations. Can we use that data then to forecast future price movements?

And this is a realm of research that’s just beginning. They’ve been studying this type of information in other markets for many years, and I do think that we are beginning to see the first inklings, and Engelberg’s paper is one of them, that this type of data can be really useful, particularly for, both for individual investors and institutional investors that actually want to create or trade on this type of information.

Engelberg is expert at the stock market, and at understanding search trends. He uses search trends as a way to gauge attention. There have been lots of attempts over the last couple of decades, we know there is a correlation between increased attention in stocks and future stock price movements. The question is how do you gauge attention? How do we know what that means? When people are more engaged, do you look at that via money that companies are spending on their marketing budget? That gets people’s attention.

Engelberg kind of synthesizes all this type of information and provides a framework that he in turn has consulted with other hedge funds to actually create actionable trading strategies based on trends in Google search data.

I think this is great, I hope you enjoy the conversation. Again, this is on my blog, Tradestreaming.com, you can come by and drop some questions or any feedback that you may have, always welcome for that. I’ll also post a transcript of this conversation at a later point. Please check in, we hope to be producing these types of podcasts weekly. Again, thanks for joining us.

*****

Let’s talk about yourself, your background, and then we can sort of migrate into this specific paper.

Professor Joey Engelberg: Sure, so my financial background really starts at the Securities and Exchange Commission. I think my title was research specialist there for three or four months, where I first got to see financial research being done at this office called OEA, the Office of Economic Analysis.

That really got me fired up to do financial research full time. I applied for a PhD program soon thereafter. I went to Northwestern, their business school called Kellogg. I received a PhD in finance in five years, and then got a job here at UNC. This is my 3rd year here.

I would say my interests in general are in this intersection of media and finance. I think in particular where social media fit in, and, specifically since you brought up the Google trends research.

There are a lot of papers in finance that write articles about what happens to prices or volatility, or some moments that returns when news or media articles are published, but there are very, very, very few articles in finance that try and quantify how many people go out and actually read them. There are just swarms and swarms of information out there, but it’s very hard to figure out what kind of information, or which particular stocks people are paying attention to in a particular day.

I can tell you that Apple had fifteen stories on the Dow Jones newswire today, but I can’t tell you how many people read them, or how many people paid attention to Apple on any particular day. The research that you’re referring to is really our attempt to go out and try and quantify something like that, because I can tell you there are lots of theories in finance about how people allocate attention, and what that means for asset prices. But empirically, it’s just very difficult to do.

In the last year or two I have been particularly interested in this sort of demand side. A lot of people though about sort of the supply side of news and media, I’m trying to think about the actual demand side, how many people are going out and actually paying attention to Apple on a particular day, and how can we go about and quantify it.

There are obviously different approaches to quantifying attention, right? I’ve seen papers in the past about how many dollars are allocated to PR, or investor relations. That’s one way to sort of generate demand. I guess that’s demand generation.

Engelberg: Sure, I agree. I would say that you sort of grouped the attention measures sort of into two camps; the first camp are these sort of market based measures. I’ll tell you in the literature trading volume is the most popular measure of attention.

But, if you read a lot of the academic literature, trading volume is a measure of lots of different things. It’s a measure of disagreement between investors. There are lots of theories that say when investors disagree about let’s say a firm’s prospects they’ll trade quite a bit with each other. There’s a large theory that uses trading volume as a proxy for liquidity, when stocks are highly liquid there’s more trading. And trading volume, I guess, is a proxy for attention.

It can’t be though, then, a very good measure of any one particular, of any one of those in particular. Right? It’s probably just a sort of equilibrium outcome of all of those things. When trading volume is high on a particular day, maybe that’s because a lot of people paid attention to that stock on that day, maybe it’s because a set of traders or funds just needed to unload a large block, maybe some liquidity reason. We don’t exactly know.

That’s why I think there’s parts of these equilibrium measures, like trading volume, some people use extreme returns as measures of attention, I think have some problems.

On the supply side, I agree with you. I’ve seen news, advertising expense, and so on in the literature being used as measures of attention. But again, the number of news articles, or the amount a firm puts into its PR or advertising doesn’t guarantee people will actually read the stories. I think it’s nice to have a measure, a sort of revealed measure, which by people’s actions, by going in and typing in APPL into a search engine, or MSFT, or ENND, or whatever the particular is, reveals that they are going out there and acquiring information about a particular firm.

One thing that we saw, and this was already back in 2007 at Seeking Alpha, was certainly an entrenched trend. As the interface to the internet moved away from sort of an AOL type model where you actually went through an ISP to get online, people were interfacing with their search engine to get online. Where people used to go to Yahoo Finance and go look up their portfolio, people are beginning to search by ticker. That was where you could see the search trends. That’s the approach you took, was to look at the Google search volume for stock tickers specifically, right?

Engelberg: Correct, and there’s a couple of interesting things to say about that. I’ve looked at these sort of tickers in Google trends or Google insights over time. I’m not sure how familiar you are with those interfaces. It sounds like you are pretty familiar. If there’s not “enough” search volume for a particular term, Google will essentially return to you a missing result, they’ll say there’s not enough search volume for your query.

I can tell you over time that there are fewer and fewer tickers for which that is true. Which I think that’s evidence for what you just said, which is that more and more people are using search engines for an interface for their ticker searches.

I could also say, we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the kinds of people that search for tickers through a search engine interface like Google. And, most of the evidence that we’ve found in terms of correlatedness with the search volume and trading suggests that those people who search for tickers in search engines are on average retail traders. The institutional traders might, presumably use Bloomberg or whatever their institutional provided interface is, but most of the evidence that we find is that Google search volume is highly correlated with retail trading.

That’s interesting. I guess a couple of years ago Google launched what is called The One Box, where instead of actually getting a link as the results page of typing in AAPL, Google was putting a real time quote there with a chart and links to other sites to do research. Clearly they were seeing that trend as well. That’s sort of a qualitative measure for me, but it was clear that they saw people were beginning to search more and more that way.

Can we talk now about some of the findings you had as you looked at this search volume?

Engelberg: Sure, I think there are sort of two main findings. The first finding is born out of that last bit that I talked about. After you sort of establish the fact that the search volume is probably a good measure of retail attention and not institutional attention, you go to the academic literature and sort of look for theories of retail attention.

And, probably the most prominent one is by a Berkeley professor named Terrence Odean. He and his partner at UC Davis, his name is Brad Barber, and their theory essentially goes like this, is that when retail traders have an attention shock, so you just flash something in front of them, you flash Apple in front of them, or you flash Microsoft in front of them, on average, they’ll be buying, and they’ll be buying because retail traders rarely short. It’s actually in the data, empirically, I can tell you retail traders don’t short very much.

So, when there are attention shocks, they can only sort of take action on those attention shocks. Suppose half the people had good feelings after the attention shock, they wanted to buy, and half the people had bad feelings, they wanted to sell. The people that can sell, given that they don’t short, given that retail traders don’t short, are the people that already own the stock. But, the people that can buy, they don’t have to have already owned the stock. They can buy sort of anything, it doesn’t matter whether it’s in their basket of stocks they already own or not. This theory from Barber and O’Dean says that when there’s an attention shock, on average there will be buying.

Another key part of the theory, which is also born out in the research is that on average, there are some guys that are good, but on average, retail traders appear to be uninformed. Thereby, on average, their buying or selling does not seem to have information in it.

Those two pieces in conjunction produce a prediction in this Barber O’Dean model, which is when there’s an attention shock, you’ll see buy, which means you’ll see prices pushed up, but if that buying is uninformative you’ll eventually see reversal.

An example of this is some other work that I have which is what happens, for example, following a buy recommendation on the CNBC show Mad Money. Empirically I’ve documented it, and now about three other people have documented it. After a buy recommendation prices spike up, but because that buying is uninformed, they reverse. Some people find they fully reverse, partially reverse, but there’s pretty strong evidence of reversal after the spike that follows a buy recommendation on Mad Money. And I think that’s another sort of classic example of a retail attention shock.

Coming back to the Google results, that’s exactly what we find. When we find attention shocks, measured as a change in the search volume from week to week for a particular ticker, so Apple experiences a large increase in SPI, in a particular week, we can predict prices being higher, so a positive return the next couple of weeks. And, then we see reversal over the next about 26-52 weeks, depending on how we measure it. That’s the first major result in the paper.

The second major result is something very similar, but among IPO stocks. Again, we can look for search volume for IPOs, obviously before a firm goes public, so before the IPO date, and it turns out that the set of IPOs that have a large increase in search volume before the IPO, and keep in mind, this is all about predictability, so there are implementable trading strategies. Zack, you had talked about trading strategies, these are all sort of implementable trading strategies, but for the set of stocks that have spikes in search volume before the IPO, those are exactly the set of stocks that have large first day returns for the IPO. But, again, there’s predictability for reversals. The set of stocks that had this large increase, this large spike in search volume and had a large first day return, when those are both jointly true, those are also the set of stocks that reverse again.

So, those are essentially the two main findings. We find this prediction for spike and reversal both unconditionally in sort of universal stocks, and then in particular for IPOs, which is the setting that a lot of people thought retail traders play a significant part in the return anomaly surrounding IPOs.

So interesting. So, you talk about these are exploitable strategies that you can create some type of methodology to leverage some of these predictabilities. Can we talk about, from the findings of the paper, what and investor would do to exploit this?

Engelberg: Sure. For the first result, that large search volume predicts temporary increases in returns, an exploitable strategy is when you see search volumes spike, let’s say from last week to this week, in the paper we look at the difference between the median search volume over the last eight weeks and this week. So, you look at the difference between sort of what the average, and here average means median, search volumes has been over the last couple of months, and see how it compares this week. When there’s a large increase, that’s when you want to be buying, because you’re predicting, you’d essentially be getting ahead of what we expect are the set of retail traders who are going to come in and buy over the next couple of weeks. And, so we see buying over the next couple of weeks.

And then second part of the strategy, after that has happened, we see reversals. You would only want to hold for a couple of weeks, or after a couple of weeks, if you didn’t buy, you would want to short sell those stocks that have large increases in search volume followed by increases in returns.

That’s the same thing for IPOs. For the set of stocks that had large search volume before the IPO, you would want to buy on the first day, because first day returns, so open to close returns for IPOs are high on that first day. And, if you saw a stock that had both an increase in search volume before the IPO, and a large first day return, so when both of those were true, you would want to short that stock going forward.

There may be some limits to you doing that. It may be that shorting that IPO after the first day might be expensive. It might be hard to borrow, that definitely may be true. I can tell you with the first results, sort of what unconditionally happens to search volume and future returns, the set of stocks for which there is the most predictability are the smaller stocks. These are the set of stocks that a.) retail traders can move, and this is true going back to the methods of the CNBC Mad Money example. The set of stocks that have the largest percent increases in returns after recommendation on Mad Money are the smaller stocks. Those are the set of stocks for which a reasonable amount of retail buying can really effect. That’s also, we also find evidence of that in our data as well.

So, like market cap under $2 billion or something?

Engelberg: Exactly, exactly. Small cap, exactly. Those are the set of stocks where you really see the spike reversal pattern. But that’s sort of a warning, because those are the set of stocks where the transaction costs are also be the highest.

What is the average outperformance? If I was to buy a basket of these types of things that your research has shown, vis a vis an index, what type of out performance, what type of return are we seeing on something?

Engelberg: Right, so we’re talking about- it’s not a huge number, we’re talking about 18-20 basis points in a period of two weeks. So, you can sort of extrapolate that, about multiply that by 26, you might be talking about around 5% or so a year, something like that.

That’s really interesting. Sorry, I cut you off.

Engelberg: No. I was saying, it may not sort of strike you as a very large number. Fortunately, we have enough data, we have enough stocks in the cross section to statistically identify it. That’s often a problem with some studies, when you have these attention events, you don’t sort of have enough data points, but fortunately, we have enough data about stocks, a cross section, to actually identify a statistically significant of 5%.

And, again, that’s a cross section, that’s including all market cap stocks? Meaning if you focus just on smaller cap stocks, can you improve that percentage?

Engelberg: Yes. If you did focus on smaller stocks, the number would be greater, but the mean result if with respect to the Russell 3000. That constitutes 90-95% of the market cap universe in US stocks. You’re right, the number would be higher on condition of the smaller stocks that you focus on, you would get greater returns. But again, you would also pay higher transaction costs.

I don’t know if this is something that you’ve focused on in this paper, or future research or someone else has done, what if you overlay other- you’re looking to define attention, but other ways to define attention, like some of the things we talked about in the beginning of this conversation, on top of this strategy? Would that boost your returns?

Engelberg: Sure. It may. I think the idea there, and it’s a good one, maybe you have an alternative measure of attention, which sort of confirms the signal that we’re talking about in Google Trends.

We haven’t done much with that, mainly because when we were writing this paper and sort of motivating it, we wanted to really push the idea that this was sort of a new and improved measure of attention, and so we didn’t think about sort of combining trading signals to get sort of the greatest profit the way, for example, a hedge fund or a mutual fund might do. The focus was more for an academic audience and introducing them to sort of an innovative way of measuring attention.

But, I think it’s a good idea.

So, just curious in terms of also focusing on search volume, obviously this is the age of social media, or what I like to call in my book participating media, are there other online ways to define attention that in the future may be even better signals of attention? Like, retweeting something, or liking something? Those are sort of trivial examples; where somebody interfaces with something a little bit more intimately that shows they may be a little more focus, I guess.

Engelberg: I think you’re right. Someone passed along a paper to me that looked at Twitter volume. I haven’t read it yet, but I think it sort of goes to your sort of broader point, which is this may be sort of the tip of the iceberg. I think search volume, tweets, and so on, any sort of actions that reveal the sort of underlying views of a broad audience I think are going to be really powerful.

That’s exactly what search volume is and what Twitter volume can be. It reveals what sort of millions of households are thinking about at a particular time, other than sort of surveying them in real time and getting enough households to sort of pick up the phone.

I don’t know another way of doing that very well. I think it is sort of the tip of the iceberg, and there absolutely could be much more to do.

Just to ask a mundane question, how would investors interested in either further researching this concept, or actually getting the Google data, where would they turn to find that type of information?

Engelberg: Sure. Google makes these data available at two places. One is a website called Google Trends. Another is a website called Google Insights.

What’s wonderful about Google is they make it freely available, so you can go to either one of these websites, as long as you’ve signed into your Google account, your Gmail account. Type in a term. It will provide this search volume index, this history of search volume, which is scaled by some number, usually the time series average of search volume over that time.

So, it will sort of be centered around one, sometimes- I think Google Insights at one point, maybe still now, scales it by the week that had the highest search volume, so that the max will be 1 or 100%. But, it will provide you that picture, and it will have a link where you can download these data in a CSV file and then just open them up in Excel and start playing with that. And, that’s exactly what we did.

I mean this was something that, what, the chief economist, Hal Varian of Google sort of intimated to the public, that this richness of data that we’re just beginning to uncover within Google?

Engelberg: That’s exactly right. Hal Varian, maybe a year ago, something like that, put out sort of a call to arms to economists that said, “Look, here’s an amazing data set that, again, can sort of reveal the opinions, interest information of a broad audience. There has got to be sort of great applications for these data.” And, he was exactly right.

I think sort of the neatest application so far- everyone is running a race to figure out how we can use these data. You probably are aware of the Nature article that used these data to predict flu outbreaks. This was an amazing idea, which is Google actually sees the IP addresses, so they can map search volume to particular areas in the country. They know whether search volume for a term in Wyoming is high, or North Caroline is high, and so on.

So, what this team of researchers at Google did, and ultimately published in this prestigious journal, Nature, they came up with a list of flu-related terms, like ‘flu symptom’, or ‘treating the flu’, things that people would search in Google if they thought they had the flu. They mapped them, via the IP addresses, to particular areas in the country. What they could show on the paper is they could predict, actually predict, flu outbreaks in the US one to two weeks before the Center for Disease Control could predict them. CDC of course gets their data from local hospitals.

So, you could image the search is sort of the indicator, the precursor. Someone searches for ‘how to treat my flu’, or ‘flu remedy’ before they actually go to the hospital and get treated, you can get these early warning signs actually from search volume for where flu outbreaks are occurring in the US.

To me, that’s an amazing sort of health/science application for these data.

But, I think it illustrates the potential for these data.

Of course Google tried to help investors along with- I guess beginning the conversation for them, launching this Google domestic trends on Google Finance, where they sort of overlay a basket of search terms by industry, by vertical industry. Have there been people that have looked is that useable information yet? Is it just sort of food for thought?

Engelberg: I haven’t looked at those data yet. The sort of closest thing I think to those data that I’ve seen is a second Google project that myself and the same co-authors at Notre Dame, who wrote the paper that we’ve been talking about, have started, which is trying to use search volume not necessarily to measure attention toward particular stocks, but to come up with new measures of you might call it consumer confidence, you might call it investor sentiment, sort of broad views towards markets, or the macro economy.

So, here the idea is when lots and lots of people are searching for term ‘bankruptcy’, or ‘recession’, or ‘credit card debit’, and so on, that gives you a good sense of sort of what sentiment in the broad market is like. Then, of course, going back to sort of getting better measures of these objects that people in the academic literature write models about all the time, once you have a very clean measure of something like investor sentiment, there’s a set of theories in the literature that you can go about and test with the better measure.

But, to answer your question, no I have not seen people use those data. The closest thing, and it’s not that close, but the closest thing that I’ve seen is in this new paper, we call it The Sum of All Fears, that tries to measure sort of consumer confidence, or investor sentiment using these search terms.

That’s so interesting. It’s very clear from this conversation you’re very passionate about your research, and the market.

I ask this same question to sort of all participants on this podcast. Where do you go for information? I don’t know if you invest personally, but what sources are you reading about the market to stay abreast of certain trends, or to get information? What tools are using in your workflow?

Engelberg: Sure. I, for whatever reason, in terms of reading I like the standard tools like Yahoo Finance, and New York Times, and so on.

But, in terms of actually getting investment advice I like looking at the raw data. So, I like taking large data sets, historical returns, looking for sort of patterns in those returns, and so on. I’m sort of less prone to take someone’s advice rather than just sort of me seeing it myself from the data. I sort of trust myself and the data work rather than investment advice. But, that’s just sort a personality quirk, I think.

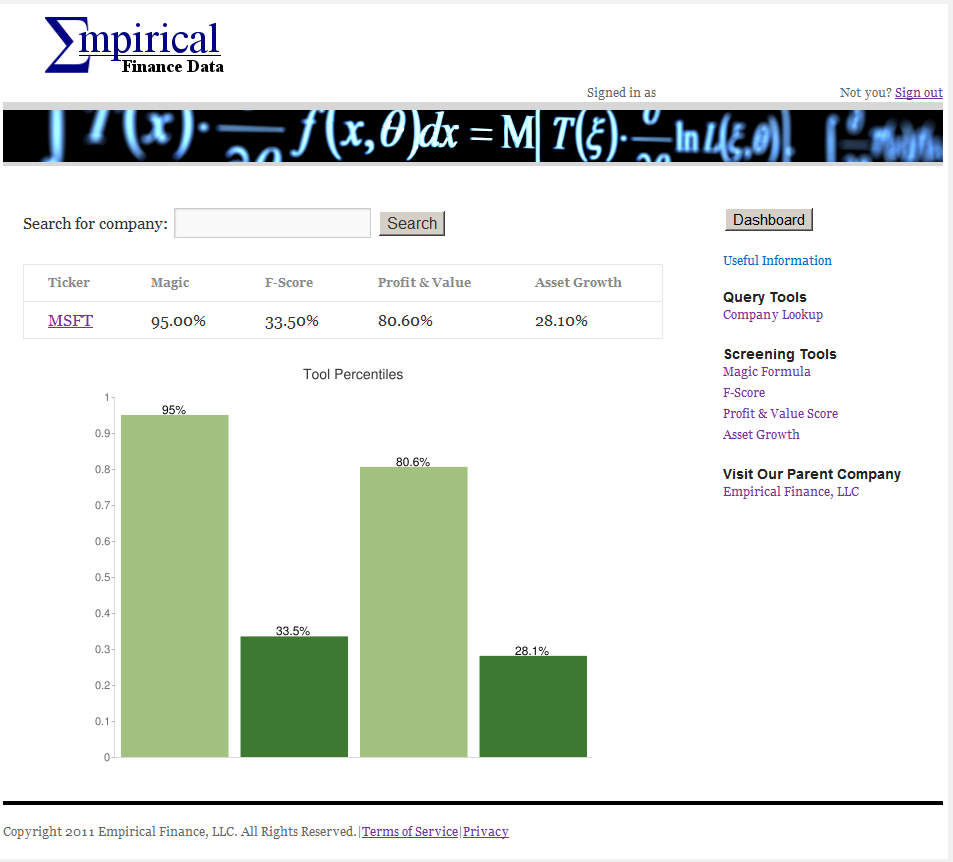

Have you heard of a firm called Empirical Finance?

I haven’t yet had them on the show. I’d like to invite them at some point. But, I think it was founded by a bunch of researchers. I guess they raised money and they basically created a fund that invests along some of the cutting edge research like this paper you put out, really to put real money behind some of the strategies.

Just curious in the academic community if people have heard sort of what they’re doing, or-? It doesn’t sound like there is.

Engelberg: No. I can tell you that certainly the Google paper that we discussed, it has gotten some attention. So, I’ve been invited to sort of present it at a couple of hedge funds, so I think there are people that are certainly interested in it. I can’t tell you the hedge fund’s name, but I know one hedge fund that is certainly trading on it. I know there is interest. I certainly know there’s interest.

That’s fantastic. Thank you so much for participating. This has been really engaging, really interesting. It’s been a great conversation.

Engelberg: Pleasure for me as well, Zack. Thank you.

That was Joey Engelberg, Professor of Finance at UNC. Very interesting conversation about Google search trends.

************

Hal Varian, Professor of Economics at the University of California Berkeley, eventually went on to become the chief economist at Google. He wrote an op-ed piece in the New York Times in 2004: “In the 1970s we saw the rise of the Wall Street quantitative analysts, then came program trading, perhaps computational linguistics and contextual data mining will become the new hot technology in the financial economics.” Perhaps that’s why just three years later Google hired him to be their chief economist.

One loss that I think we had to this system was actually Facebook. Facebook had a system called Lexicon early on, where they were actually providing some of demographic associations, sentiment pulse mapping type information. I assume eventually they will open that up again and charge people to access it. But, that would have been a treasure trove of information for investors.

Again, I’d like to thank Professor Engelberg for participating.

This podcast you’ll find on iTunes, or on my website, Tradestreaming.com. Please stop by and leave any comments you may have. We look forward to hearing from you in the future.

Resources:

- Listen to the podcast

- Subscribe to Tradestreaming Radio on iTunes

- Professor Engelberg’s homepage

- Engelberg’s paper: In Search of Attention (Engelberg, Da, and Gao) (.pdf)

- More episodes of Tradestreaming Radio

- Google Insights for Search