5 trends we’re watching this week

Every week at Tradestreaming, we’re tracking and analyzing the top trends impacting the finance industry. The following is a list of important things going on we think are worth paying attention to. For more in depth trendfollowing, subscribe to Tradestreaming’s weekly newsletter (published every Sunday).

1. Banks increasingly moving in on the pureplay marketplace lenders (Tradestreaming)

While the marketplace lenders like Lending Club and Prosper are putting competitive pressure on traditional banks, the incumbents are responding in time, with the help of firms like LendKey, which provide the electronic platforms to banks to conduct online lending.

2. Stock markets increasingly interested in blockchain technology (CoinDesk)

A group of banks, exchanges and clearing houses has formed a working body to discuss how blockchain tech might be used in settlement.

3. Fidelity not renewing its partnership with roboadvisor, Betterment (RIABiz)

While both parties touted this relationship between old and new, it appears Fidelity is close to launching its own version of an automated advisory platform that it’s built in house.

4. MIT launches its first graduate fintech course (paymentweek)

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the most prestigious universities in the world, is launching the first graduate level financial technology course in the United States. “Throughout the course’s seven weeks, students will explore different sub-industries within the FinTech space, including consumer finance, payments, etc.” Where do we register?

5. How Riskalyze’s Aaron Klein is giving investors permission to ignore short-term risk (Tradestreaming)

“People got a real thrill out of investing in 2013 and didn’t get quite as big of a thrill in 2008. That’s not risk tolerance — it’s market outlook.” Riskalyze helps advisors manage portfolio risk for $121 billion in assets.

The online investing course — with Mesh Lakhani

It isn’t every day you stumble upon your doppelganger.

Mesh Lakhani may very well be mine. He’s the investor and author behind the Future Investor Course (www.futureinvestor.co ), a great new course that teaches all about online investing tools like Wealthfront, Acorns, Betterment, and more.

Mesh joins us to discuss his personal journey to adopting these tools and how today’s investors are using them. Check out the interview.

About Mesh

Mesh Lakhani is an investor, a teacher, and the founder of the Future Investor course.

Mesh Lakhani is an investor, a teacher, and the founder of the Future Investor course.

Listen to the FULL interview

Resources mentioned in the podcast

- Future Investor Course (Mesh’s course)

- @meshlakhani (Mesh on Twitter)

Even more resources

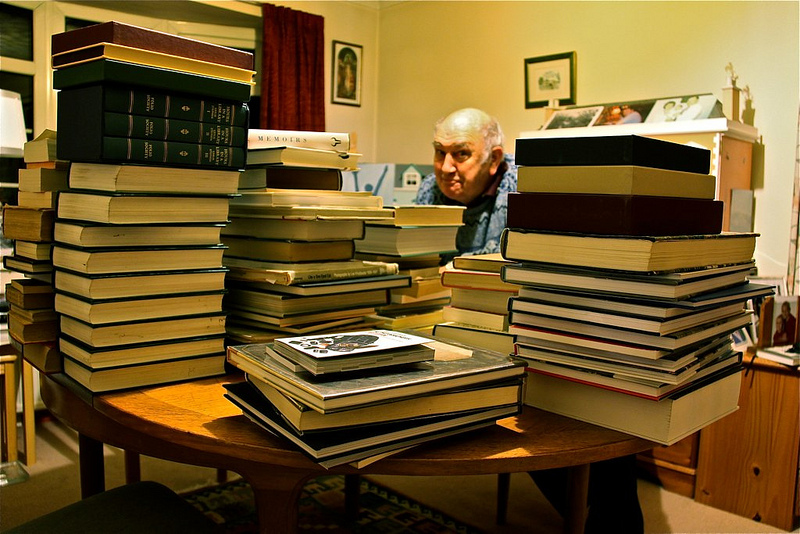

Photo credit: ♔ Georgie R / VisualHunt.com / CC BY-ND

Top 12 Investing Tools of 2012

2012 was in many ways uneventful for those of us looking at the investing tools space.

Maybe it was general yawning at the stock market and less participation/caring about investing.

Or maybe it was because little capital flowed to new, innovative investment tools this year (a few existing companies like Betterment raised money).

That said, many of the existing investing tools in the marketplace are maturing. Products are getting easier to use and in general, gaining in popularity.

Here’s a group of 12 tools (you’re welcome to add more below) that I believe were worth your attention this past year (I’ve interviewed many of the founders of these companies on my podcast). They are a smattering of new tools (like SmartAsset) and older ones (Lending Club just celebrated its 5th year anniversary) that keep getting better with time.

Curious as to what you think — full disclosure: I was an early hire at Seeking Alpha and still own woefully too few shares and I’ve consulted to Wall Street Survivor and Lending Club.

Top 12 investing tools of 2012

(in no particular order)

- SmartAsset: So smartly designed and so necessary, it’s a shame SmartAsset didn’t launch years ago. It’s like a Web 2.0 financial calculator that provides personalized advice to help answer the most common of financial decisions like “should I rent or buy?“.

- QuantBlocks: QuantBlocks is a cool and powerful platform to help design and test quantitative trading strategies. The best part is that it doesn’t require any programming expertise. It’s just drag-and-drop simple.

- Seeking Alpha Pro: Recently launched, the price-point (around $200/mo) and the quality of the research on Seeking Alpha Pro makes it primarily for professional investors. Of higher quality than general posts on SA, Pro is intended to raise the bar of Seeking Alpha’s exclusive content and cement its role as the open destination to head online for stock research.

- Wall Street Survivor: Wall Street Survivor is the investor’s CodeAcademy. It’s designed for beginners and intermediate investors alike. WSS provides very specific, action-based missions for learning the ins-and-outs of investing.

- Motif Investing: Motif Investing is a platform for idea-driven investing. If you’re looking to create a low-cost portfolio of stocks around a specific idea, Motif is pretty interesting.

- SprinkleBit: SprinkeBit has bold goals and that’s to provide a one-stop-shop for younger investors. It combines the social sharing and learning with a brokerage platform.

- Reading the World: Russel Redenbaugh’s new newsletter is based upon decades of experience with policy-driven investing. It examines big macro trends and how government/economic policy impacts such movements.

- OurCrowd: There are a lot of crowdfunding platforms waiting for the JOBS Act to really hit but OurCrowd is already up and running and funding some top Israeli startups. For accredited investors only, investors can build a startup portfolio with increments as small as $10k.

- Lending Club: The peer lending network just celebrated its 5 year anniversary and $1B in assets. Together with smaller competitors, the peer lending industry is underwriting about $100M in loans every month now. LC Notes are becoming de rigeuer in diversified income portfolios (where else can you find high single digit, low double digit returns right now?).

- Estimize: Crowdsourcing really works and that’s true for earnings information. Estimize has shown that it’s frequently more accurate than Wall Street when it comes to financial estimates.

- StockRover: StockRover is a financial data portal that was built by a techie investor for others like him. If you enjoy deep diving into the data and doing great stock screens, StockRover is really powerful.

- Kivalia: Investors with assets in retirement accounts get the short end of the stick. They lack good advice. Kivalia is changing that with an advice layer on 401ks that tells investors what and when to buy — down to advice on which mutual funds they should own.

[listly id=”2hk” layout=”full”]

What tools/platforms did you enjoy this year? Let me know.

Company Profile: Betterment

Name: Betterment

Website: www.betterment.com

What it does: Betterment has one of the easiest-to-use, slickest interfaces to manage a balanced portfolio for long-term investors. Fund your account (you can automate this) and dial in your preferred risk mix and Betterment chooses a basket of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) for your portfolio in accordance to Modern Portfolio Theory. You don’t ever need to decide on what to buy if that’s not your thing.

Particular strengths: For investors who don’t want to be overwhelmed with investing decisions or jargon about individual securities, Betterment has done a really effective job removing the confusing part by getting investors to focus on what really matters: setting goals, focusing on time-frame, and risk.

How popular is it: As of November 2011, Betterment reported that it had 10,000 accounts and $36 million under management.

The Company

Management: Betterment was founded by Jonathan Stein, an experienced professional on the technology side of the financial industry.

Company Size: Betterment has 10 employees (Source)

Outside Investors: Bessemer Venture Partners led an investment round of $3 million at the end of 2010.

Competitors: As an online investment advisor, Betterment competes with Personal Capital and Wealthfront.

Will the future of wealth management really be “virtual”?

I’ve been chatting with a few friends over the past couple of days about which model will prevail for wealth management in years to come.

2 sides to the argument

Essentially, there are 2 sides to the argument:

- virtualists: The virutalists are banking on a future where investment advisors will prospect, deliver advice, and service clients over virtual channels (Internet, phone, chat, video conference). This is a boundary-less marketing environment and doesn’t put a premium on marketing to a local clientele. That’s a world where there’s no tennis, no kids’ bar mitzvas, and certainly, no shoulder-crying on your advisor when markets go bad.

- ol’ skoolers: This camp doesn’t envision a world where the delivery of financial services changes very much from what it’s been traditionally. Advisors have adopted email and websites and yes, are beginning to use social networks but ultimately, it’s a face-to-face business. You may buy diapers online but you’ll never really buy financial services online.

It might be easy to dismiss the ol’ skoolers as just that — financial dinosaurs who just can’t face the digital future of the business. We’ve got plenty of analysis like this from kasina pointing to the future and it appears to be digital: Continue reading “Will the future of wealth management really be “virtual”?”

Betterment vs. Wealthfront, per their CEOs

There’s a very interesting conversation happening over on Quora about the merits of the two online investing services: Betterment and Wealthfront.

What makes it even more compelling is that it’s being held between the CEOs of the two firms, Jon Stein and Andy Rachleff, respectively.

Betterment’s argument

Stein (Betterment) used the following framework to describe why he thinks Betterment is the better solution:

- automation: Users seem to agree that Betterment is better integrated and more fully automated

- for serious investors: There’s more personalization available for Betterment users, as you can change your allocation and make trades square away.

- integration: Probably related to #1, but Betterment is both a broker and investment advisor, which means everything is branded Betterment, making a smoother ride for clients (Wealthfront uses Interactive Brokers as its brokerage and clients have to contact IB with questions on the actual account).

- better deal: lower fees

- tuned to behavioral finance: Betterment realizes how poorly most of its users would probably behave so it uses smart defaults to automate decision making.

- customization: Instead of just getting a model portfolio like you would at most RIAs, you can tweak things on Betterment to get it just the way you want.

Rachleff (Wealthfront) counters

Andy takes a different approach when sizing the two firms up. Here’s his framework why Wealthfront beats out Betterment.

- focus: WF targets young tech employees.

- sophistication: WF uses Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and therefore, Betterment should return less for every level of risk.

- determination of risk: WF uses a 10 question survey to set risk parameters and allocation while Betterment requires you do it yourself.

- minimums: $5k minimums at WF and they don’t charge until a client tops up to $25k or more. Betterment charges a subscription fee for small accounts.

- fees: it’s interesting to see that both firms feel they’ve got the better model here

- transparency: you get an allocation and portfolio recommendations before you open an account with WF, which you can then take and manage yourself. At Betterment, you don’t get rec’s until you open.

Of course, CEOs should behave as beknighted cheerleaders of their firms, so readers should understand where both Jon and Andy are coming from.

But what an awesome world we now live in where CEOs are engaging in the conversation to help users/investors understand which investing platform is right for them.

Read What are the main differences between Betterment and Wealthfront (Quora)

***FYI, I was contacted by Betterment’s Community Manager with the following clarifications:

Betterment is actually founded on modern portfolio theory. As you mentioned, it is intersected with Behavioral Economics so people actually implement the practices of MPT.

Regarding risk – Betterment makes recommendations for allocation based on goal type, time to goal i.e. if saving for retirement in 30 years, I can allocate more to stocks, say 80% stocks, 20% bonds. If saving for a major purchase, Betterment would recommend I allocate more conservatively. Then, the product shows me, in real time, the best and worst case scenario. Based on this information, I will understand my appetite for risk, and adjust the sliders accordingly.

6 easy ways to get more interested in investing

I live and breathe this investing stuff.

So, sometimes I take my insane fervor interest in investing for granted.

But a lot of people aren’t me (thankfully). Many are either too busy, too distracted, or uninterested in investing. That’s a shame — because outside of building your own wealth, there isn’t an easier way to protect your (small) fortune and grow it over time.

So, why are so many closed out of investing? Why do 40% of 18-30 year olds NEVER want to participate in the stock market??

That’s a post for another time. For now, I want to focus on how to get more interested in the stock market, assuming that’s a worthy goal (I think it is).

How do you create interest in something you aren’t quite interested in to begin with?

Here are 6 ways to get more interested in investing

1. Get seriously informed about the market: In 1921, Harry Kitson wrote a book he thought was destined to help college students improve their study habits. Nah, it’s really a book about the science (hey, it’s close to 100 years young) of learning. How to Use Your Mind addresses the hard question of finding inspiration in learning. For Kitson, people don’t generally start with inspiration about learning. It’s about perspiration — working hard to learn a bit about a subject. The passion soon follows. (Source: How to Use Your Mind)

2. Look deeper: So much of what we know about the stock market is through our perception and personal histories. Maybe our parents were involved or maybe they were disinterested. But to create true, motivated interest in a subject, it takes changing our mental image, looking at investing differently. My grandfather was a Buffett-like figure but the markets today would have completely confounded him. I know is sounds kind of Zen-y but, “If you’re really paying attention, you can always go deeper, continuously. If you do, new worlds open for you..” (Source: Quora)

3. Think good thoughts about the market: Negativity totally breeds negativity. Sometimes that may be warranted but most of the time, it clouds our thinking. The best investors I’ve met are always objective about their investing approach. They don’t let bad decisions wrack them. They move on, learning from their mistakes. The market is a great teacher and it demands its participants visualize success. Learning with passion about the market requires:

- OUR choice: we practice because we want to, not because we’re forced to

- build success on success: find ways to have success, however small. The positive feedback loop is powerful.

- purpose to practice: underscoring everything should be a strong feeling of personal purpose. Answer the question why investing matters to you, (Source: Steve Pavlina)

4. Find friends who like the market: Not only does this stimulate a desire to learn about and participate in the market, it may improve your results. All else equal, social  households — those who interact with their neighbors, or who attend church — are more likely to invest in the stock market than non-social households. It even extends to where you live — people living in states where people are likely to invest are themselves more likely to invest. Mutual fund managers who live in the same state are also more likely to trade the same stocks. We’re social animals and we learn from our friends. Investing ideas and education spread epidemically. We’re influenced by others’ behavior. Want to learn more about investing? Surround yourself with people who do, too. (Source: Social Interaction and Stock Market Participation)

households — those who interact with their neighbors, or who attend church — are more likely to invest in the stock market than non-social households. It even extends to where you live — people living in states where people are likely to invest are themselves more likely to invest. Mutual fund managers who live in the same state are also more likely to trade the same stocks. We’re social animals and we learn from our friends. Investing ideas and education spread epidemically. We’re influenced by others’ behavior. Want to learn more about investing? Surround yourself with people who do, too. (Source: Social Interaction and Stock Market Participation)

5. Use resources at work to dive in to investing: Just like having neighbors you can shoot the sh*t with about stocks, the market, and investing, your work environment can impact your learning about the market. Sure enough, employers that offer seminars on investing find their employees more educated about investing and more likely to invest. (Source: The Effects of Financial Education in the Workplace)

6. Try some new tools: The finance industry is not your father’s finance industry. You don’t have to work with cigar-smoking old dudes who wear suspenders. Platforms like Betterment simplify investing and make it easier to focus on the important things. Others like Personal Capital make it easier to get professional investment advice online. SigFig, Jemstep, and FutureAdvisor help to find waste in your portfolios and optimize them for performance. There’s a renaissance of investing tools that can help.

Don’t feel bad if you’re not all that into the markets. That distance is actually a good thing — it can make you a smarter, more objective investor. But like everything worthwhile in life, investing is a lifelong process of learning: learning about your own behavior and others.

You can do it, Slugger.

Making investing simpler – with Jon Stein

A lot of people don’t invest because it’s seemingly too complicated.

So many decisions to make, so much jargon, who to trust?

Jon Stein is the founder and CEO of Betterment which he describes as a mix between Apple and Vanguard. It’s extremely easy to design a fine portfolio.

By removing much of the noise that distracts investors, Betterment has developed a 95% solution for 95% of investors. Plus, the firm is rolling out some functionality for investors who want a little more flexibility.

Jon’s growing an online asset manager from the ground up. He shared with me that Betterment has almost 10,000 customers already with mid-$20M under management (AUM), with many of them using the goals and planning tools the site has developed.

Jon joins us for this week’s episode of Tradestreaming Radio.

Continue reading “Making investing simpler – with Jon Stein”

How to make Betterment better (Hint: truth in marketing)

Sometimes, it’s worth reading the fine print — especially, when it comes to financial products.

I was interviewed by Mint.com recently about my thoughts on Betterment, a startup that performed pretty well at recent tech conference, TechCrunch Disrupt (see, Betterment wants to be your new, higher-yield savings account).

What is Betterment?

Well, it’s really an investment advisory service that masquerades as being a better savings account. By removing much of the jargon (the site doesn’t even mention securities by name), Betterment removes many of the barriers to putting money in the market. As I said in the Mint interview:

For most people, opening an online trading account and figuring out what to buy and who to listen to, there’s so much noise out there.

And that’s true: how many individuals really understand asset allocation, diversification, risk when professionals  have such a hard time defining them? It’s kind of like I know it when I see it. Betterment provides a usability layer that requires only one decision point: what percentage of my money do I want in the market? That’s it.

have such a hard time defining them? It’s kind of like I know it when I see it. Betterment provides a usability layer that requires only one decision point: what percentage of my money do I want in the market? That’s it.

Removing the confusing jargon and the pain points associated with complicated concepts is ultimately a good thing. I can just picture my grandparents trying to navigate an E*Trade account trading screen.

Oops, it’s not actually a bank account

While pursuing a noble end (making investing easier for the mass majority), Betterment stumbles when it positions itself as an alternative to a savings account. It is most definitely NOT a savings account. Money in Betterment is split between Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), one of which will include U.S. Treasury Bonds if you allocated to that. That means, an account holder

- risks losing some, if not all, his money

- will see fluctuations in the account

- will have investment-level taxes on gains

I was quoted in the interview:

“They took a process that’s inherently scary and overwhelming for people and used technology to simplify it,” says Miller. “I think that’s an honorable thing. But to market it again and again, to talk about a savings account, is just disreputable. It’s scary, actually.”

Though it appears that they’ve toned it down recently, there’s still just too much talk/discussion on the Betterment website about safety and savings. Betterment may be a great product to *invest* spare cash just sitting in a savings account (much like ShareBuilder used to be).

Just don’t compare it to the savings account. At 90 basis points (.9%), it’s also expensive.

—> Like what you see? Hey! Don’t forget to subscribe to the free Tradestreaming newsletter for updates, tips, and special offers.

Source

A Better Savings Account? (Mint.com Blog)