Payments

How Canadian banks dominated peer-to-peer payments

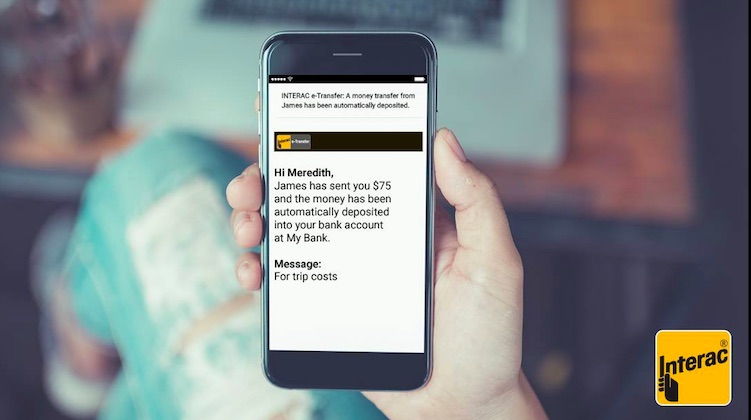

- Interac e-transfers, Canadian banks' peer-to-peer payments tool, have the lion's share of the market because the banks got in the game early and acted in a coordinated fashion

- Well before the peer-to-peer payments tool was launched, Interac was a known and trusted payments brand in Canada -- an important factor driving adoption