The U.S. bank branch footprint is shrinking as digital banking grows. U.S. banks closed a net 944 branches through the third quarter of 2024, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. Wells Fargo has closed the most branches, shuttering 188 branches over the past 12 months.

There’s less demand for branches in certain markets, too. As digital banking accelerates and consumer behaviors evolve, financial institutions are re-evaluating the role and necessity of their physical footprint. That’s because people are banking differently. Banking used to be something you did as an errand in your town. Now banking is something you do, not somewhere you go.

71% of Americans choose to handle their bank accounts through mobile apps or computers and this behavior is most notable among consumers of major banks like Bank of America and JPMorgan, according to the American Bankers Association.

And it’s these big money center banks that are leading a lot of the branch closures.

“If you think about a lot of the big banks, they have banking service centers in major cities. That was built for an era where you would be walking down Main Street, and say, ‘Oh, let me stop in and talk to my banker about a mortgage.’ That’s not how people bank anymore,” said Matt Britton, CEO of Suzy, a SaaS market research and consumer insights platform.

Technology and consumer behavior is driving change

Several fundamental shifts are accelerating the transformation of branch banking:

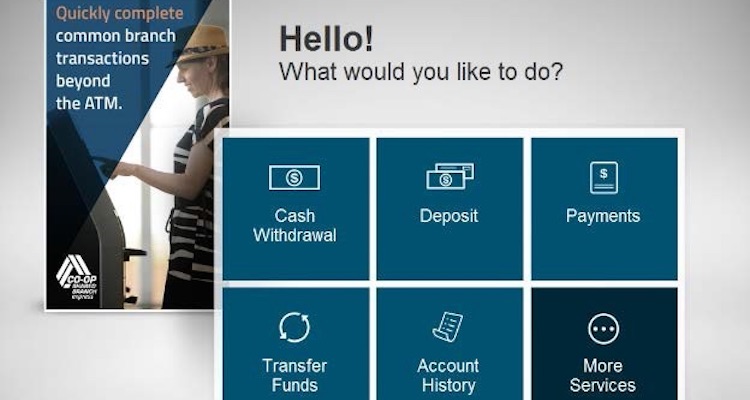

- Digital banking adoption continues to grow: Consumers increasingly prefer mobile and online banking for routine transactions, reducing the need for physical locations. Younger bank customers, in particular, prefer the digital use of debit cards and BNPL. Amazon’s ease of use and personalized recommendations have raised the bar for banks.

- Cash, no; Digital, yes: The declining relevance of cash questions the fundamental need for physical infrastructure. “I question if they’ll even be ATMs or cash in five to 10 years. Why does cash even exist? It’s such a legacy system,” Britton shares.

- Competitive pressure from digital banks: The rise of digital-first banks like Chime and Nubank demonstrates the viability of branchless banking models. These competitors, built for young people and the underbanked, operate without the burden of legacy systems and real estate.

Implications on banks

Traditional financial institutions, like banks with branch networks, face several critical strategic considerations:

Grow their core value proposition: Branches made it historically easy to bank. ATMs made it even easier. But as digital banking proliferates, it’s never been easier for consumers to do core banking transactions. That means banks that want to compete for the long term need to reassess the value they provide, particularly around consultative services.

“If you don’t need an ATM, if you don’t need consultative services…if you don’t need a physical banking location that you can step into, then actually, why do you need a bank except to store the money that you have?” Britton asks.

Improve service delivery: As a way to differentiate, banks should develop new models for delivering high-touch services traditionally provided in branches, particularly for complex products like mortgages and wealth management. In fact, according to a recent report by PYMNTS, subpar mobile apps is one of the top two reasons 1 in 5 credit union consumers switched financial service providers in the last year.

Some financial institutions understand that branches provide an opportunity to improve the customer experience across channels. U.S. Bank uses its physical locations to educate consumers on how to self service. If a customer comes in regularly to deposit checks, for example, it isn’t uncommon for someone at the bank to demonstrate how to do remote check deposit. Other banks, like Citi, are using its branches to spur conversations around complex issues, like mortgages and wealth management, that are harder to have over a phone or computer interface.

Upgrading digital Infrastructure: Banks’ Investment priorities should shift from physical infrastructure maintenance to digital platform development and enhancement. Over a decade ago, U.S. Bank began rebuilding its digital infrastructure in a way that would enable it to more easily partner with fintechs and launch new products. This investment is paying off as the firm has launched a variety of new products and services to its business customers over the past couple of years.

Although fewer in number, branches are unlikely to be completely phased out. They do provide needed services for specific demographics, like older customers, and for more complex products. Big brands are opening up new branches as they shutter old ones. Chase, for example, has plans to open 400 new branches in states like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, even while it closed others in consolidated markets. In 2024, PNC Bank announced a nearly $1 billion investment to expand its branch footprint, opening over 100 new locations and refurbishing more than 1,200 existing ones by 2028.

Download the Suzy whitepaper, featuring its proprietary data and expert advice from CEO Matt Britton on how financial institutions can stay competitive and connect with younger audiences.